Raptors: Enraptored: Leonard Baskin’s winged creatures suggest human triumph, defeat

Published in the Gazette on Thursday, July 21, 2011. Article by Phoebe Mitchell.

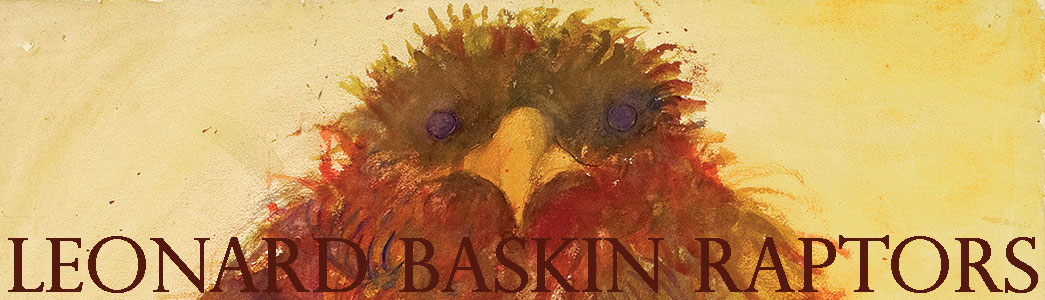

NORTHAMPTON – Mention the word raptors in the same breath as the name of the late artist Leonard Baskin and a bold, ruffled-fe athered, somewhat sinister owl might come to mind.

In fact, Baskin’s work includes a panoply of raptors and other  birds of prey, from whimsical and cartoonish to mythically elegant. A show on view at R. Michelson Galleries in Northampton through Sept. 30 presents the full range of Baskin’s raptors as they evolved over four decades, from the 1940s through the ’80s.

birds of prey, from whimsical and cartoonish to mythically elegant. A show on view at R. Michelson Galleries in Northampton through Sept. 30 presents the full range of Baskin’s raptors as they evolved over four decades, from the 1940s through the ’80s.

Baskin, who earned an international reputation as a sculptor, book illustrator, wood engraver, printmaker, graphic artist, writer and teacher, lived for many years in Leeds with his wife, Lisa Baskin. He died in 2000 at the age of 77.

Called simply “Raptors,” the exhibit illustrates Baskin’s artistic genius, which conjured up images that speak to viewers who have only a fleeting knowledge of art history, literature or philosophy as well as to those who recognize the allusions that infuse his work.

Raptors were central to Baskin’s work throughout his career. His winged creatures stood on their own, as subjects in their own right; Baskin also incorporated them in other images, most notably his human figures.

Birds of prey – owls, herons, eagles, pelicans – encapsulated his antithetical understanding of the human race: noble and base, common and heroic, tender and brutish, vulnerable and ruthless. With that in mind, the crow is a frequent subject in his work. Outcast because of its scavenging ways, the crow stands in for the downtrodden, the common people who survive by their wits on society’s castoffs.

In a famous collaboration, Baskin joined forces with British poet Ted Hughes to create “Crow: From the Life and the Songs of the Crow,” a 1973 collection of Hughes’ poetry which explores a crow-inspired mythology illustrated with Baskin’s drawings.

‘In a horrible way, marvelous’

In the Michelson show, a small woodcut from the 1950s called “Dead Bird” shows what looks like a lifeless crow on its back, its legs in the air. Baskin renders its features in bold, black lines that fit together like slivers of glass to form ragged wings. Its legs extend upward to talons that are curled in death, but still malevolently clawlike.

The bird is both defenseless and undefeated, a presence even in death.

Baskin wrote about his fascination with raptors: “Owls obsess me. They’re predators, always in control and always mysterious. Late one midsummer night I watched one for two hours. He was after the thousands of moths who were drawn to a light by my window. He grabbed at them with his claws, never missing a one, and their wings fell off all over his breast. He was beady-eyed and, in a horrible way, marvelous.”

In the ’60s, Baskin probed more deeply the relationship between humankind and raptor in works like the “The Great Birdman.” A large black-and-white woodcut, the piece presents what looks like a burly man’s muscled torso with a raptor’s head. Rendered in broad, curving strokes, the imposing figure recalls history’s bigger-than-life heroes and villains: Mussolini, Balzac, Churchill, H.G. Wells, men who were variously brilliant, courageous, cruel and unforgiving.

The pieces suggest that genius is complicated and comes at a price.

In the following two decades, Baskin broadened his exploration even more, using color and, at times, a softer line to depict raptors. In the watercolor “Burgeoning Phoenix,” Baskin tells the story of death and rebirth via a bird cloaked in multicolored feathers. Like the fire it rose from, this bird is a deadly force, a metaphor for the awesome power of imagination.

There are also more whimsical works, including the watercolor “Capricious Punch,” showing a long-legged bird with the legendary trickster Punch – another of those lovable yet violent characters – astride its back. While brilliantly plumed, this bird, too, comes with talons worthy of an eagle.

Baskin’s extraordinary mastery of diverse mediums – sculpture, painting, etching, engraving, woodcuts, watercolors, drawings – is also on display. In all of them, he holds nothing back. His artwork takes risks – as it must – to present his unsparing look at humankind and its attempt to find meaning in mortality.

Among the show’s most striking works are three side-by-side images of raptors. Each bird faces the viewer eye-to-eye, filling the picture frame. While the works are about 2-by-1½-feet square, these raptors look massive, as solid as sculpture, and timeless.

Here, Baskin seems to say that the creative force – the best of what makes us human – will endure despite the vagaries of history and mortality’s relentless march. Certainly, as this show amply illustrates, these images carry on Baskin’s unique vision, an artistic legacy that continues to shape our vision of humanity, past, present and future.

The gallery, located at 132 Main St. in Northampton, is open Mondays through Wednesdays from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.; Thursdays through Saturdays from 10 a.m. to 9 p.m.; and Sundays from noon to 5 p.m. For information, call 586-3964 or visit www.rmichelson.com.