Leonard Baskin: Baskin and Politics: An Exhibition on the 100th Anniversary of His Birth

August 15, 2022-October 31, 2022

Reception Friday September 9, 2022, 6-9pm in conjunction with Northampton’s Arts Night Out

August 15, 2022 marked the one hundredth anniversary of Leonard Baskin’s birth, a century rife with political strife and violent conflict, circumstances that Baskin never shied away from in his work. Though his works often teeter with ambiguity, Baskin was never unclear about his purpose. He stated in 1959 in a Time Magazine interview:

The forging of works of art is one of man’s remaining semblances to divinity. Man has been incapable of love, wanting in charity, and despairing of hope. He has not molded a life of abundance and peace and he has charred the earth and befouled the heavens more wantonly than ever before. He has made of Arden a landscape of death. In this garden I dwell, and in limning the horror, the degradation and the filth, I hold the cracked mirror up to man. All previous art makes this course inevitable.

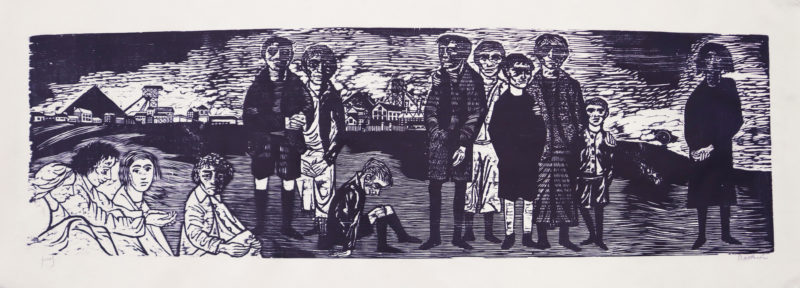

Much of Baskin’s work was overtly political. He constantly gravitated towards the marginalized, always illuminating the plight of the persecuted and exposing the tyrant, though he was aware of how easily the oppressed could become the oppressor. Early in his career he espoused overtly Marxist ideals. His pre-1949 wood sculpture, Pelle the Conqueror, depicts the eponymous protagonist of Martin Anderson Nexø’s great proletarian novel from Denmark. Baskin’s early fascination with Marxist ideals shaped a great deal of his printmaking in the 1940’s and 1950’s, while setting the stage for his later work.

Early Political Works

18 in, wood, circa 1948

36×24 in

8×5.5 in

8×5.5 in

35×23 in

Works from the 1940s and 1950s, especially the woodcuts, were highly influenced by the German expressionists. They showed the average worker, downtrodden and living in a world beset by tyranny and oppression.

FDR Presidential Memorial

The Franklin Delano Roosevelt Memorial was unveiled in 1997 by President Clinton and stands at the edge of the cherry tree walk on the Tidal Basin. Baskin’s funeral cortege, a 30ft long bronze relief at the last room of the memorial, shows a horse-drawn casket followed by mourners. Baskin said of Roosevelt “he was the first person I ever voted for and the only person I ever voted for who got in. He was the last great president this country has had.” While the actual funeral roped off the mourners to either side of the road and the horse-drawn casket was followed by limousines and official delegations, Baskin decided to let the “common people” take their proper place in the procession. When interviewed at the unveiling he said of his motivation, “Just think of the wars around the world right now. . . Such a happy time we are living in? What should I do? Still life of grapes and mussels? No.”

Watercolors and Prints

30×22.5 in

30×22.5 in

22.5×30 in

21×14 in

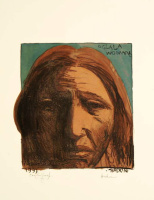

Native Americans

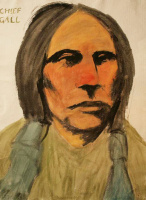

Leonard Baskin’s interest in nineteenth century Native Americans was roused into acute attendance from ignorant indifference, when the National Park Service commissioned him to provide illustrations for the handbook that described the then-called “Custer National Park”, now “Little Bighorn National Monument”. Baskin’s detestation of Custer was as near instantaneous as was his respect for the people of the Sioux. From Hollywood’s distortions, cliches and prevalent bad slogans of the time, Baskin’s insight into the vast, resolute, and wanton destruction of our native populace was matched by his deepening regard for the wisdom and courage of the Sioux and other Indian leaders.

30×22 in

31×23.5 in

15×11 in

30×14.75×18.75 in

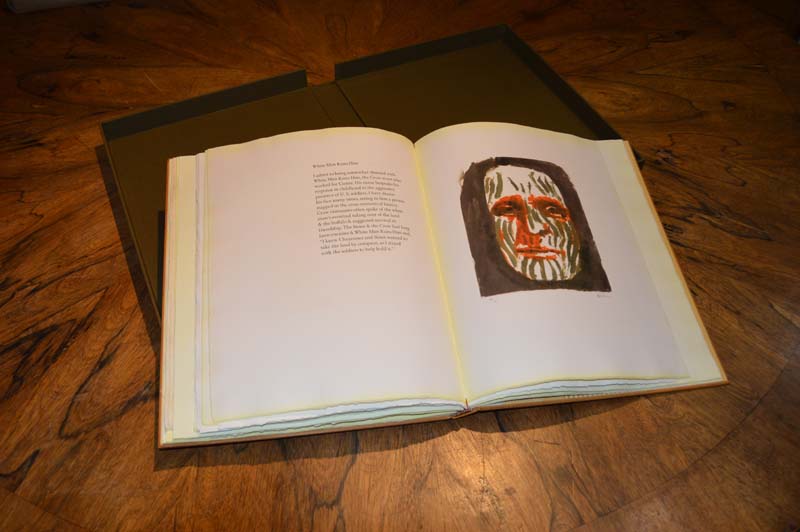

A Book of Plains Indians

Words and Monotypes by Fritz Scholder and Leonard Baskin

Published by the Gehenna Press in 1994

Baskin and Scholder met several years before, introduced by a mutual friend, art dealer Bill Bishop. Scholder had been influenced early on by Baskin’s work and eagerly accepted an invitation to come to Massachusetts to collaborate on a major Gehenna Press project. Both night owls, they worked late into the night and each contributed monotypes to this exquisite volume. Expertly printed by Michael Kuch in a quantity of twenty-six.

See images from the book here.

Racial Equality

The Gehenna Tracts

Between 1970 and 1975, Baskin collaborated with his close friend, University of Massachusetts professor Sidney Kaplan, to produce a series of books called the Gehenna Tracts. This was an attempt to make available important but difficult to attain early radical writings. These included works by American abolitionists and women’s rights advocates.

The first of the Tracts was The Selling of Joseph: A Memorial. Leonard commented:

The series of tracts represented an attempt to make available works that touched in a cricial way a moment in the history of the struggle from freedom & a more just ordering within society.

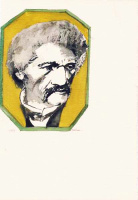

Samuel Sewell (1652-1730) was a businessman, printer, and Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Superior Court of Judicature, the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s high court. He was involved as a judge in the Salem Witch Trials, a role for which he later publicly apologized. The Selling of Joseph is the earliest-recorded anti-slavery tract published in America.

This edition comes with an engraved portrait of Sewell.

Charles Brockden (C.B.) Brown (January 17, 1771 – February 22, 1810) was another writer almost lost to history who championed the rights of marginalized classes, having written early texts on issues of gender equality and the abolition of slavery.

Alcuin: A Dialogue is one of the earliest American texts on the rights of women. The book had never been printed in its entirety until the Gehenna Press published it in 1975.

Of the book, Baskin wrote:

C. B. Brown, our first professional writer, whose gothic novels the printer had avidly read, had also written the first American book supporting the rights of women, never printed in its entirety until this edition. The discovery of his texts was by accident, in the memoirs of a rare book dealer [it is extraordinary how boring these memoirs of an exciting trade tend to be]. Under the guiding aegis of Sidney Kaplan the complete work was assembled. It was edited by Lee Edwards and was an innovative and contributive addition to the subject. A popular edition was issued based on the Gehenna book.

This ink drawing was reproduced and appears on the title page. The original drawing is included with this edition.

Two Essays on Slavery by John Woolman

This edition has a hand-watercolored title page signed by Baskin and includes the original ink drawing reproduced within.

The Woolman was the third & last of The Gehenna Tracts. It serves, as do its predecessors, in making available {especially as this text was popularly reprinted from our edition} works which are difficult to readily obtain. This was Gehenna’s second Woolman text; earlier it had issued a large broadside of a nightmare of Woolman’s entitled ‘The Fox and the Cat’; the press’ editor rescued it from the obscurity of earlier Quaker journals.

– Leonard Baskin, The Gehenna Press: The Work of 50 Years 1942-1992

John Woolman (October 19, 1720 – October 7, 1772)

JOHN WOOLMAN’S DREAM OF THE FOX & THE CAT –

Jackie Leach Scully describes Baskin’s broadside in her book, Good and Evil: Quaker Perspectives:

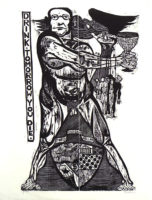

There is a woodblock print by Leonard Baskin of ‘John Woolman’s Dream of the Fox and the Cat’ which creates a vivid illustration of Woolman’s awareness of horrible injustice in the world. In the woodcut’s foreground is a vicious fox-cat with bared teeth and claws, and in the background is the figure of a hanged ‘old Negro man’ whose flesh was to be fed to the fox-cat. In Woolman’s narrative of the dream there is the further addition of a woman calmly drinking tea, who looks on from the position of privilege (as do perhaps the viewers of the woodcut and the readers of the Journal) unmoved by this violence against a fellow human being. Woolman writes that in the dream, ‘I stood silent all this time and was filled with extreme sorrow at so horrible an action and now began to lament bitterly. . . but none mourned with me.

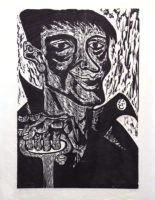

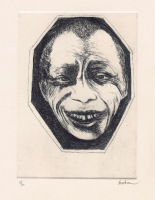

THE SHERIFF – Modeled after Lawrence A. Rainey, the sheriff alleged to be involved in the Freedom Summer Murders where three civil rights activists were murdered by the Klu Klux Klan in Neshoba County, Mississippi. Baskin was ever conscious of the role of the powerful and how easily they could become the tyrant.

21×19 in

18×18 in

5.25×2.75 in

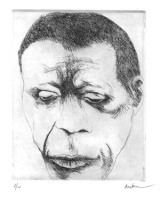

Baskin did many portraits of homage throughout his career and he also collaborated with those artists whose work moved him. He had planned to do a collaboration with James Baldwin, with etchings to complement Baldwin’s unpublished poems. The two had become friends when Baldwin had seen and complemented Baskin’s publication of Othello. Unfortunately Baldwin died before the project could be completed and the book, Gypsy became a memorial volume with Baskin providing etched portraits of his friend.

11.5×7.5 in

11.5×7.5 in

11.5×7.5 in

7.25×5 in

7×5 in

The image of the hanged figure showed up again and again over the years. It was an ambiguous symbol for Baskin, something unnatural but evoking divergent reactions. Was this justice for a criminal? A suicide? Or a innocent victim? In the 1950s when Baskin’s first hanged figures were created, the image of a lynched victim would not have been unfamiliar and its use would have overt political connotations. He continued to use the image throughout his career.

67.5×21.5 in

23.75×17.5 in

19.5×15.5 in

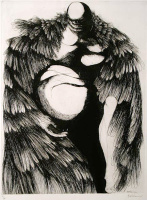

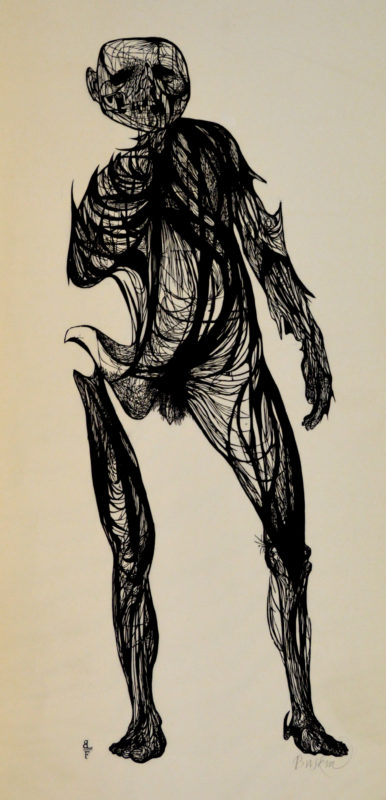

Anti-War

Baskin often referred to the idea of “man’s inhumanity to man” and there is no greater inhumanity than the horrors of war. His works on the subject are mostly unspecific to place or time but reference corpulent and overstuffed figures of a Death that has eaten so much it can no longer move. One work that was more specific was The Hydrogen Man, done in 1954 in response to the detonation of the Castle Bravo hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. A human figure with veins and sinews and its skeletal frame exposed but deformed and misshapen. Even his earliest monumental woodcut, the Man of Peace is a lone figure imploringly holding up a dead bird while enmeshed in a menacing mass of barbed wire.

60×31 in

17.75×11.75 in

23.75×17.75 in

20x15x15 in

62.25×24.5 in

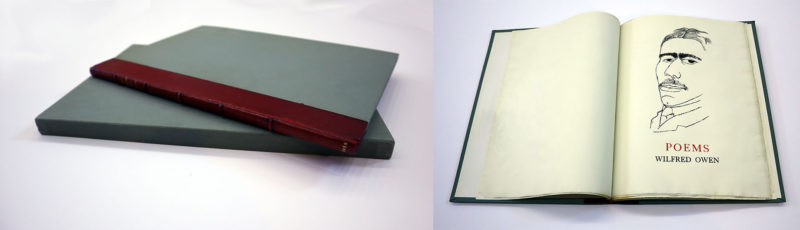

Thirteen Poems by Wilfred Owen, Gehenna Press, 1956.

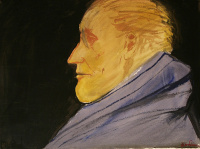

Baskin’s edition of the English anti-war poet’s verse was an early publication of the Gehenna Press. It is also a product of Leonard’s friendship and partnering with fellow artist Ben Shahn whom he considered a mentor. Shahn, Baskin said, was “the finder of the means to successfully communicate and express social and political content of an immediate and complex nature.” Baskin convinced Shahn to do drawings for Wilfred Owen which were painstakingly reproduced in the book. The portrait of Owen on the title page was engraved by Baskin from Shahn’s drawing on the block.

Representations of Women

In the early decades of Baskin’s career his subjects were overwhelmingly representations of male figures. Female subjects were often biblical or from Greek mythology. Beginning in the 1960s and for the rest of his life, there was an outpouring of images of women. The Vietnam War era saw a proliferation of social and political unrest over gender inequality and women were increasingly seen as bearing the burdens of poverty and war. Starting with his controversial and unrealized war memorial sculpture for the peak of Mt. Greylock in the Berkshires of Massachusetts, he repeatedly depicted women in mourning, their anguish and sorrow ever present.

Throughout his career, Baskin often made portraits of artists that he held in high esteem. Well before the art-historical mainstream recognized the work of women artists throughout history, he depicted those pioneering female figures whose work had not received the recognition it deserved.

17×11 in

27.5×20 in

30×22.5 in

10.5×14 in

10×15 in

17.5×12 in

Monument to Labor

Baskin’s 1971 bronze was a response to seeing nineteenth century realist sculptor Jules Dalou’s unfinished Monument to Labor (Monument aux Travailleurs). Dalou, along with several other artists including Auguste Rodin, worked on ideas to develop a public monument to celebrate the growing labor movement in the urban areas of France. As early as 1889 Dalou traveled across the country to sketch workers and transformed them into clay figures. His plan was for a large column emblazoned with workers tools in relief with workers of every aspect of labor in French society all around. He died before he could complete it and after his death in 1902, the sketches were cast into bronze.

Baskin’s Monument to Labor was also unfinished.