Barry Moser: The Pennyroyal Press

The first imprint from the Pennyroyal Press Death of the Naricisus in 1970 (though his first printed book – through the Castalia Press – was The Red Rag in 1969.) Since then, Moser has produced dozens of fine press books and broadsides and is known as one of the country’s foremost bookmen.

in Wonderland

and What Alice Found There

or, The Modern Prometheus

Huckleberry Finn

View Barry Moser Speaking about the Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland series here

A Brief History of Pennyroyal Press

by Barry Moser

The first book bearing the Pennyroyal imprint was published in 1970. It was a portfolio of “botanico-erotic” etchings by Barry Moser called The Death of the Narcissus. The etchings and typography were printed by Moser, then a fledgling printmaker and printer. The typography consisted of a half-title page, a title page, a haiku poem by Onitsura (a seventeenth century Edo poet), and a colophon. But the very first book Moser printed was James A. M. Whistler’s essay “The Red Rag.” It was printed on the same press a year earlier under the imprint of Castalia Press.

The events that led to that first book began in 1967. Moser had moved from Tennessee to New England and was teaching at The Williston Academy in Easthampton, Massachusetts. He was soon befriended by Louis Smith, a glazer, framer, and print collector who bought a few of Moser’s early prints and subsequently introduced him to Leonard Baskin. That meeting led to Moser’s studying with Baskin, and those studies eventually led him to visit the Gehenna Press and to meet Harold McGrath. That was in 1968. Walking into the pressroom of Gehenna Press on a dark November afternoon, Moser says, “was like walking into another age. It was like being transported to a former life. It was as if I knew all the sounds and smells and artifacts of such a place when, in fact, I knew nothing of them. But, I had a very deep and moving—almost spiritual—feeling that I knew this environment in some previous life or something.” The effect was indeed so profound and enticing that Moser quickly convinced the headmaster at Williston that the school could no longer exist without a printing press and some type. That led to the acquisition of a press from a job printer, Fred Rau, in Turner’s Falls, Massachusetts. It was a 12 x 18 Chandler Price clamshell press and came with a fair run of Goudy Oldstyle, a good amount of worn type, useless fonts, and all of the other typical typographic odds and ends that one would expect. Williston’s Headmaster, Phillips Stevens, gave Moser a room in the corner of the old Easthampton railroad station to set up the small shop, and it was there that new types were acquired and that first slender volume, The Red Rag, was printed.

A few years earlier the building that housed that first Pennyroyal pressroom had been given to Williston by George Alpert, a lawyer who helped to found Brandeis University and who was also the president of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad. His railroad company owned the building before it was given to the school. George Alpert’s son, Richard was an alumnus of Williston and that was, at least in part, the reason for the gift. Richard Alpert later became well-known as the Baba Ram Dass, and, in collaboration with Timothy Leary, Ralph Metzner, Aldous Huxley, Allen Ginsberg, and others, formed the Castalia Institute in Millbrook, New York in 1963. Those connections led to the student press at Williston being dubbed The Castalia Press. Moser fully intended that this would also be his imprint as well, but the academy’s business manager informed him that to do so would be a violation of the school’s non-profit status. And so Moser had to come up with another name for his printing and publishing enterprises.

Having illustrated his first book in 1969, The Flowering Plants of Massachusetts (Vernon Ahmadjian, University of Massachusetts Press, eventually published in 1979), Moser became enamored of plants and plant lore and as a result named his press after a plant, Pennyroyal (Mentha pulegium), a magical plant that is common to the gardens of the practitioners of the so-called Dark Arts. The art of printing is often called the Black Art, and that, combined with the fact that the word Pennyroyal itself had interesting connotations for Moser (the desire to do something regal, but having only pennies in his pockets with which to do it) made it seem, at the time, a natural choice. It was done, and in 1970 Pennyroyal Press published its first book, The Death of the Narcissus, under that imprint.

That same year Moser began graduate studies in printmaking at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst where he studied with Jack Coughlin and Fred Becker. On the verge of giving up on trying to master that famously difficult medium of wood engraving, Becker, a master wood engraver himself, encouraged Moser to persist. And persist he did.

Working with a fellow teacher at Williston, the Rev. Douglas Graham, a retired Headmaster of the Cheltenham School in Britain and a close friend of Samuel Beckett, Moser produced another slender volume of engravings to accompany a few Greek epigrams celebrating Bacchus that Graham translated from the Greek Anthology. Thus the second Pennyroyal book was published, Bacchanalia, and it was the first Pennyroyal book to use wood engravings as illustrations. (NB: The frontispiece portrait of Whistler that appears in The Red Rag is not an engraving. It is a line cut made from a scratch board drawing.)

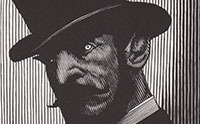

Pennyroyal continued to produce a few slender volumes for the next nine years, the most ambitious of which was Twelve American Writers, a collection of quotations about writing by writers from James Fennimore Cooper to Ernest Hemingway. Portraits of the authors accompanied the quotations. It was bound by David Bourbeau, a young protégé of Arno Werner, whose workshop was in Pittsfield, Massachusetts.

In order to pay the bills for this more ambitious project Moser invited twenty-six individuals to become Patrons of the Press—one for each letter of the alphabet. This group included a cop, an electrician, a paper salesman, a high school teacher, a civil rights consultant, and a few local business people. In exchange for a modest sum of money ($500.00), Moser promised to offer every subsequent Pennyroyal book to them at a significantly reduced price. Thus, with the financial aid of the Patrons the era of Pennyroyal’s “slender volumes” came to an end in 1979.

Some of the books of Pennyroyal Press gained modest attention in the private press world during those first nine years, notably in the pages of Sandra Kirshenbaum’s “Fine Print: The Review of the Arts of the Book.” While Moser was on a trip to San Francisco in October, 1977, Ms Kirshenbaum held a dinner party in Moser’s honor. Among the guests, most of whom were well regarded in the world of San Francisco’s fine printers, was Andrew Hoyem. Hoyem invited Moser to visit his shop the next day and Moser gladly accepted, excited to see the former workshops of the Grabhorn brothers. During that visit Hoyem asked Moser if he would be interested in doing one hundred engravings illustrating Arion Press’s forthcoming Moby-Dick. The story of that production is now well known and needs no further expansion here. The importance of the publication of the Arion Press Moby-Dick had profound ramifications for Pennyroyal Press in that, afterward, Moser reasoned that he was as capable of designing a book as was Hoyem, and that his pressman, Harold McGrath, who was widely considered as the finest letterpress printer in America at the time, was certainly as good as any of Hoyem’s pressmen. And so Moser determined to produce something on his own that was grander than any of his previous “slender volumes,” and as grand and beautiful as the Arion Press Moby-Dick.

Historically speaking, this was an interesting time in Moser’s transition from an academic artist into a full-time artist with no safety net of a teaching position to fall back upon. Baskin had taken the Gehenna Press to Devon, England and leaving all the printing equipment to Harold. Nevertheless, McGrath was facing unemployment – or worse, retraining as an offset printer. Pennyroyal may have never grown beyond a very small private press had Jeff Dwyer, a bookshop owner and nascent entrepreneur; John Lancaster, Keeper of Rare Books at Amherst College; Ruth Mortimer, Keeper of Rare Books at Smith College; McGrath (to whom all of the old Gehenna Press equipment had been bequeathed by Baskin); the poet Chase Twichell ( a protégée of Kim Merker); and a local businessman, John Locke, and Moser not formed the Hampshire Typothetae, a commercial venture whose aim was to bring in enough work to keep McGrath in a paycheck each week. It was a worthwhile effort that kept McGrath printing and simultaneously provided Moser with a place to develop his art and Pennyroyal Press. During that time, Moser continued to teach at Williston, but the stage was set for him to move away from the safe academic life, just as the stage was set for making the transition to the grand book.

Moser and his colleagues sent out a questionnaire to sellers of rare books across the country and in Europe—especially a group of loyal book and art dealers who specialized in finely crafted books that had been selling the Pennyroyal titles over the years—asking the question “If Barry Moser and Pennyroyal Press were to do one of the following books, on a large scale, which title do you think you would enjoy the greatest success selling?” The list included, among others, Thoreau’s Walden, Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels, and Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. The quorum was for Alice, though there were many warnings to “do anything, but don’t do Alice.” Pennyroyal Press did do Alice in 1982 and subsequently won the 1983 American Book Award for the trade edition of it that came out from the University of California Press in Berkeley, California.

From there Pennyroyal published four more large-scale volumes in quick succession: Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking Glass and what Alice found there in 1982; Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus in 1983; Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in 1985; and L. Frank Baum’s The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, also in 1985. The funding of these projects was done with the investments of more than one hundred fifty limited partners from around the country. They provided Pennyroyal with over a million dollars in investment support so that Moser could leave Williston, become a full-time artist/printer and thus move Pennyroyal to this next level.

Unfortunately the sales of the Pennyroyal Alice were not equaled by any of the subsequent large-scale volumes. And after The Wonderful Wizard of Oz appeared in 1985, Pennyroyal Press found itself once again in the business of printing smaller, less ambitious volumes for the next ten years.

Then that situation changed dramatically in 1995.

Sometime in the early seventies, a panel on “the art of the book” was convened at the Leverett Craftsmen Center in Leverett, Massachusetts. Fritz Eichenberg, David Bourbeau, Carol Blinn and Moser were among the presenters. Questions were taken from the audience after the presentations were concluded. One question was addressed to all: “If you could do any book in the world what would it be?” Eichenberg and Moser answered first — and in immediate unison: “The Bible,” they said. It was not a new thought for Moser that evening, because he had been dreaming of doing a Bible ever since he learned how to set type and print books. After all, as it has been well said, the road of the history of fine printing is paved with the spines of Bibles. And Moser, having taught himself the nuances of book design by studying those great Bibles of the past (coupled with the fact that he, as a youth, had been a Methodist preacher who fell in love with the King James Bible) and had set his eyes, his dreams—timorously at first—on doing one himself. After all, a fully illustrated Bible had not been done in the twentieth century, and time to do it, if it were to be done, was drawing seriously nigh.

At about the time he was working on Huckleberry Finn the matter of printing and illustrating a Bible came up in conversation with a casually dressed young man at an exhibition of Moser’s work at the Gotham Book Mart in Manhattan. His name was Bruce Kovner, and hearing of the “project,” he said that he might be interested in backing such an enterprise. But at the time Moser was reticent: good engraving blocks were becoming increasingly scarce, Harold McGrath was going to retire soon, and Moser said that at the time he felt that he “was not ready, not old enough, not experienced enough.”

Kovner demurred and told Moser that if he ever changed his mind to contact him.

In the summer of 1995, Moser was trying to figure out how to finance such a huge project without forming another limited partnership. His old friend, Jeff Dwyer, recalled the Gotham Book Mart meeting and suggested that Moser contact Kovner. He did, and on Thursday August 11, Kovner called to ask questions about the proposed project, to hear descriptions of the project, and to have some “numbers” run by him. At the end of the conversation Kovner left it by saying that “in principle” he would agree to be the “bank” for the project.

Moser later reflected: “I am old and experienced enough now, maybe. In fact, I think that everything I have ever done in my life has led me inexorably to this time and to this project. Military school and its drilling, which I am sure has something deeply and nascently profound to do with my affinity for type and pages. My religious experiences as a young man — especially the fundamentalism I ardently embraced, so that I could later move beyond it. Taking Greek at the University of Chattanooga. Having married a woman who was later willing to move to New England, a place neither of us had ever even visited. Being introduced to Lenny Baskin in 1967. Meeting Harold McGrath and seeing fine books for the first time in my life at the old Gehenna Press. I am scared now. But I hope it flies.”

It flew, and in 1999 Pennyroyal Press, using the imprint Pennyroyal Caxton (Kovner’s corporate name is the Caxton Corporation), published its magnum opus: the only fully illustrated Bible of the twentieth century, a Bible the New York Times suggested might just be “the Bible for our time.”